Using our skills as technologists to protect the equal rights of users

As developers of web applications and websites, we create interfaces for people to use (for the most part). In doing so, we have a responsibility to make our applications not only usable by those people, but also to avoid infringing on their rights. In the tech industry we’re very often in positions to make an impact, so let’s talk about what this can mean for us and our users.

Civil rights are the rights of individuals to receive equal treatment, and to be free from unequal treatment or discrimination based on a protected characteristic like race, disability, gender or sexuality.

This means citizens should receive equal protection under the law, regardless of their abilities, what they look like, or who they love. People have fought for our civil rights–from housing to employment and education–and those rights will be eroded if we don’t continue to fight for them. Improvements in these areas are for the common good. As they say, equality is not like slices of pie: more rights for people of protected classes do not mean legal rights are taken away from someone else.

In this post, we’ll discuss the potential impact of web interfaces on users’ civil rights, particularly where it meets digital accessibility, but we can’t cover it all. There are also other areas relating to civil rights that could be deserving of your time as technologists: elections and voting rights, security, legal services, government, housing, healthcare and AI to name a few. If fighting for your users’ rights intrigues you, find subject matter that aligns with your passions and experience and you could have an impact there, too. Regardless, after reading this article, I hope you’ll seriously consider protecting your users’ civil rights in the craft of any digital user interface. It could be as simple as populating non-discriminatory form options, like the case of Facebook ads and the Fair Housing Act; but we’ll also discuss ways to make an impact with JavaScript.

Once we understand how people’s’ rights might be affected by the interfaces we put out into the world, we can start to make a difference–so that’s what we’ll discuss in this post. We’ll focus mainly on web development with JavaScript because of its reach, but some of these principles will apply no matter the specific technology.

JavaScript is ubiquitous

Imagine you’ve built a sizable web application entirely with JavaScript, pulling in dependencies from the open source ecosystem and rapidly producing a draggable/droppable user interface. Accessibility wasn’t considered in the design or development phases, and auditing the code for security was demoted on the priority list in favor of shipping new features. Your team was never given adequate time to go back and fix the technical debt acquired from the very beginning, yet development marched on. Eventually, frustrated disabled users and their representatives brought legal action to try and improve things. To make matters worse, you’ve also had to deal with the fallout of a security breach. Both of these things could have been avoided with some attention paid up front to the rights and needs of your users.

Web developers rely on JavaScript to do many things, from managing our projects’ dependencies and build systems to rendering entire user interfaces. As one of the most widely deployed programming languages in the world on both the client and server, JavaScript is ubiquitous. JavaScript can impact our users’ civil rights to physical and mental integrity, safety and privacy, as we’ll discuss in the following paragraphs. These rights are often interconnected, particularly in the context of digital experiences.

In the United States, there are a number of federal, state and local civil rights laws on the books that impact people’s lives every day. You might even recognize some as relevant to discussions we have repeatedly in tech (equal pay, age discrimination, family leave, etc.). These laws can come up in a number of settings: including, but not limited to, developing software for the federal government, education, and employment. Throughout the public and private sectors, the risk of legal action can be a good motivator to protect users from discrimination through our code, and rightly so.

Learn more about accessibility compliance: https://www.deque.com/accessibility-compliance/

The Right to Be Free from Barriers to Access

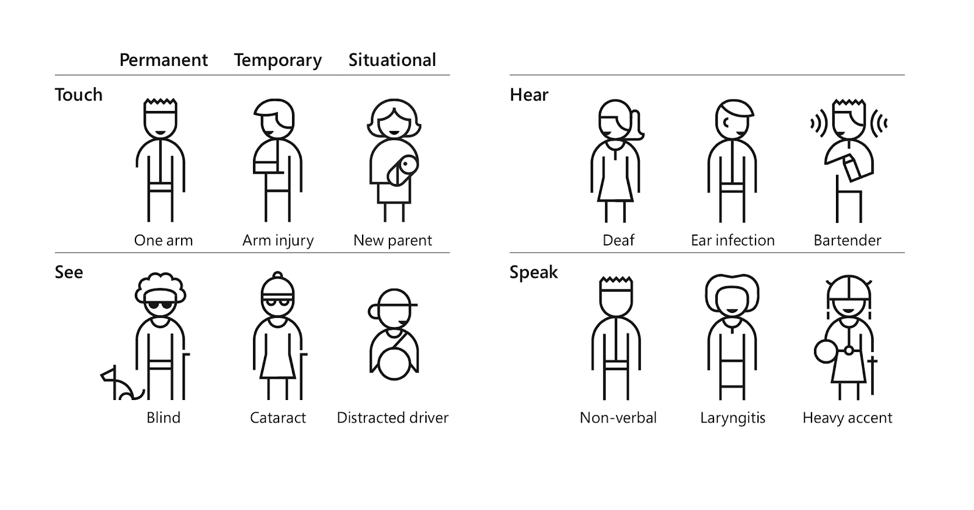

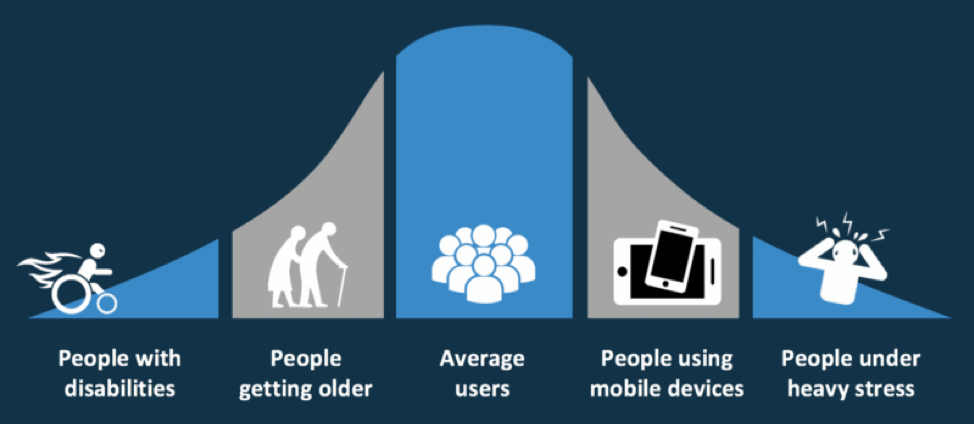

It’s not too difficult to imagine relying on software programs to do your job, given our heavy usage of online productivity tools and IDEs for programming (amongst other things). Many of these modern applications make heavy use of JavaScript to compose UI components and make smooth network updates in the background. If you have a disability–whether permanent, temporary, or situational–an inaccessible software application can make it extremely difficult or impossible to do your job effectively. Inaccessible software can also prevent a disabled person from getting a job at all, when they could otherwise contribute skilled work and more diverse perspectives.

Find more personas in the Microsoft Inclusive Design Toolkit (PDF)

As designers and developers of software, we act as gatekeepers in people’s lives more than we realize. When done right, our software could be the difference between someone with a disability living an independent, productive life, or needing outside help to complete a task, including at their job. From banking, to grocery shopping to collaborating online, accessible software can range from somewhat convenient to a total game changer helping someone to excel in life. This applies to all digital experiences, for both contributors and authors as well as consumers.

For example, people with disabilities work with content management systems all over the place, but particularly at universities with platforms like WordPress and Drupal. If these systems aren’t designed and developed for accessibility from the ground up, an update to a new JavaScript-heavy user interface can severely impact someone’s education or job performance. Accessibility isn’t just a “nice to have”; it can affect everyone’s livelihood, including people with a range of disabilities (vision loss, inability to use a mouse or a trackpad, cognitive impairments, and more). Knowingly or unknowingly putting barriers in place that disproportionately affect access for people with disabilities–or any other protected characteristic–is discrimination, and it’s definitely something to worry about.

No one automatically knows about digital accessibility, so don’t be discouraged if you have zero knowledge or experience with the subject. It’s something we all have to learn and work at, and we have to start somewhere! Over the past few years I’ve talked to many people who, after hearing about accessibility for the first time, have enthusiastically taken up the cause in their own organizations. Some have even become accessibility champions throughout the web development industry, and our collective reach has undoubtedly made an impact on the lives of users with disabilities. (Join us in the web-a11y Slack!)

“I’m disabled and I can’t use this site, why don’t they want my money?!”

It’s also true that some teams need more incentive to actually improve accessibility in their own organizations. So here’s some incentive: without attention paid to accessibility, your application and content may discriminate against people with disabilities. Not only does that carry a higher legal risk, but you’re also likely missing out on customer spending no matter what country you’re in. In the US alone, people with disabilities control over $645 Billion in disposable income. That’s a pretty large demographic to leave behind.

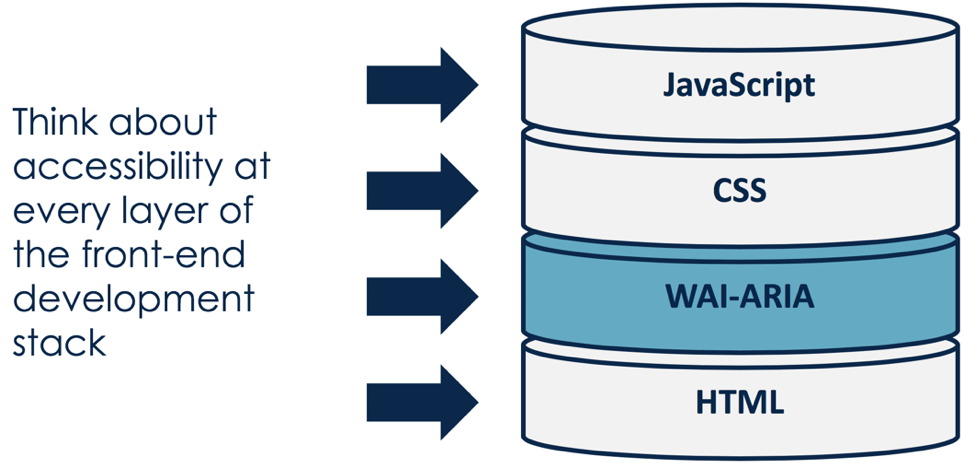

JavaScript Accessibility Considerations

For developers of JavaScript-heavy applications, all accessibility basics apply. We can make a huge impact by paying attention to things like color contrast, keyboard support & visible focus states, semantic HTML structure, form labels, and text alternatives for images and media content. Beyond the basics, common technical JavaScript accessibility requirements include:

- Focus management of layers and modals. You’ll need to be familiar with tools like `document.activeElement`, `element.focus()`, and listening for key events.

- Fully disabling inactive layers and components with CSS `display: none` and `visibility: hidden`, HTML attributes `tabindex=”-1”` and `aria-hidden=”true”`, or the `inert` attribute with a polyfill.

- Announcing view changes & asynchronous updates to assistive technology using ARIA Live Regions.

- Gracefully handling keyboard focus on deletion or removal of DOM nodes.

- Correct use of ARIA states, roles and properties.

- Automated software testing for accessibility.

Read my latest blog post for extra tips on accessibility in JavaScript-heavy applications: https://www.deque.com/blog/accessibility-tips-in-single-page-applications/

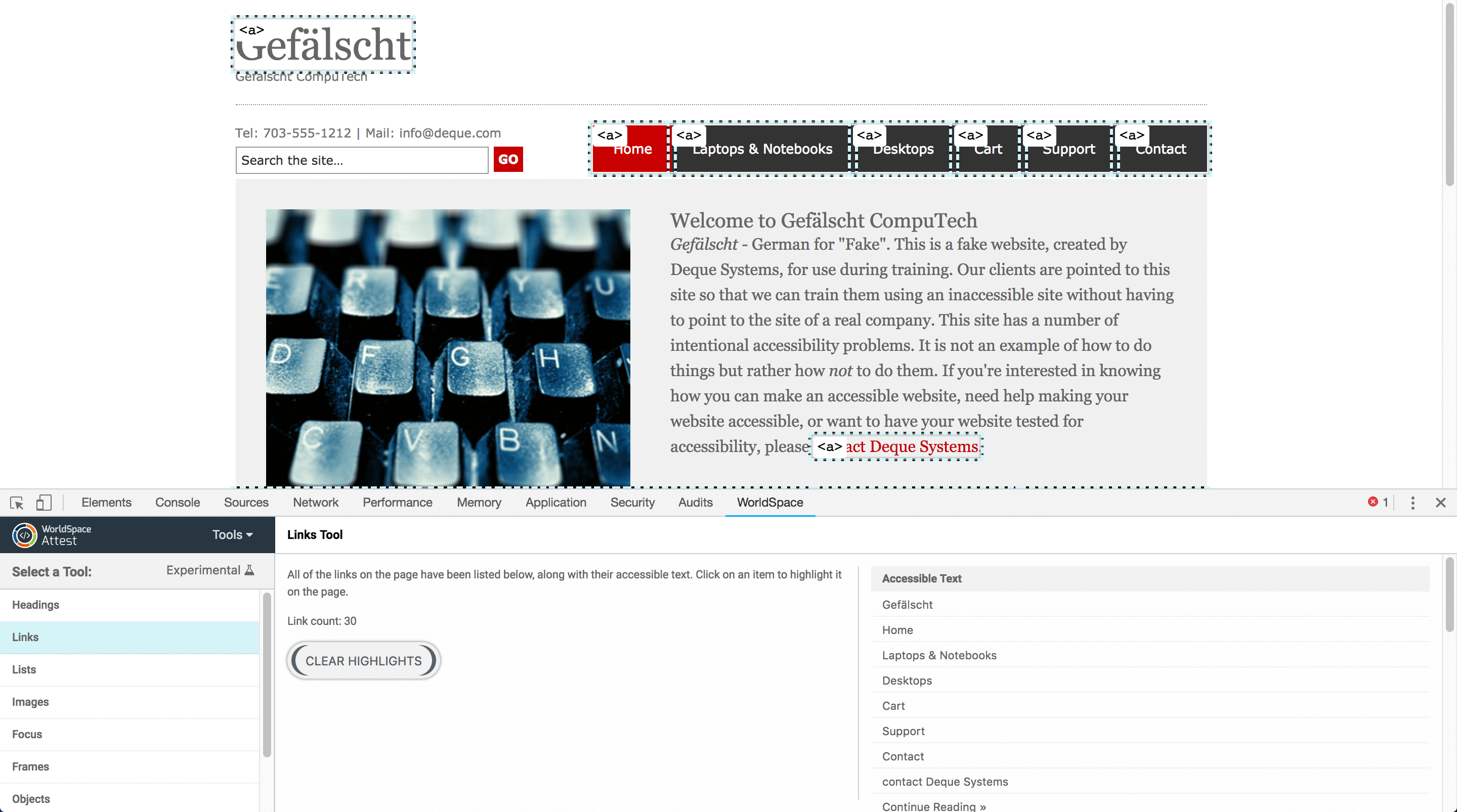

Fortunately, these days it’s easier to achieve a baseline of accessibility with modern testing tools and procedures. Deque has a number of resources and tools to help with this, including Deque University, axe (powering the accessibility portion of tools like Lighthouse and webhint.io), and the entire WorldSpace product suite, amongst other great tools throughout the industry. However, at the end of the day, what matters most is that we improve things for users with accessibility needs, rather than what tools we use to get there.

Accessible JavaScript Starts with UX

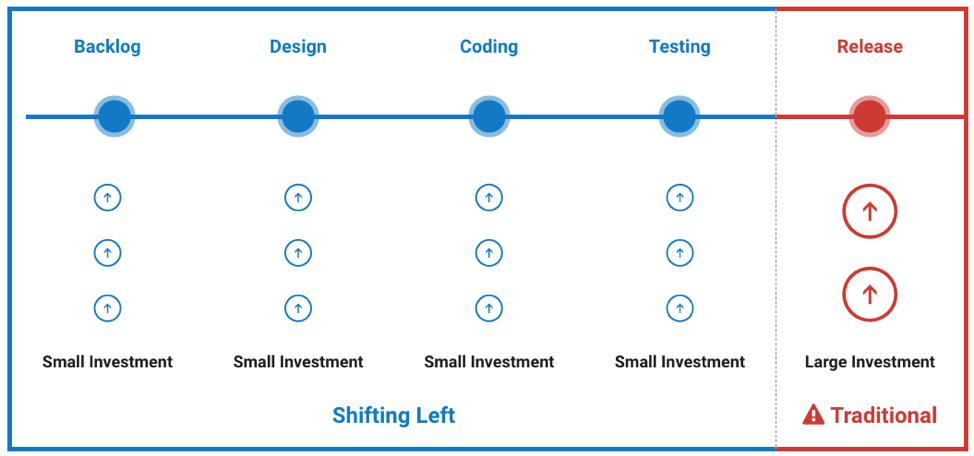

We can talk about the technical aspects of accessible JavaScript all day long, but to truly remove systemic barriers to access in our software we must first consider accessibility in UX and Design. To quote Cordelia McGee-Tubb, “accessibility is like a blueberry muffin—you can’t push the berries in there afterward.” As a JavaScript developer, let me also tell you: there are some things you can’t solve with code alone.

Say you’ve implemented a user interface design heavy on mouse interactions, with click and drag events all over it. As a developer adding “accessibility support”, you try throwing some more JavaScript event handling at it, and you quickly find conflicting key shortcuts and complications in assistive technologies: accessibility bug whack-a-mole ensues. Aside from the feasibility and cost to develop and maintain, these kinds of interfaces are often less intuitive and more complicated for users with disabilities.

“Power user” requirements with obscured controls, subtle design treatments, and forced “discoverability” don’t succeed in making your app cool and elite if they also make it much harder to use. Requiring memorization of excessive key shortcuts when the equivalent mouse flow is effortless is a display of power imbalance. It exposes a bias toward the designers and developers of said software over actual users who can’t know it as intimately as the team who created it: obscure icon buttons with no visual text labels also come to mind.

Organizations can combat bias by testing applications early and often with users with disabilities and taking their feedback seriously. Maybe you can’t redesign your entire application at once, but you can identify ways to simplify and streamline the experience in core user flows, replacing some of it one sprint or dev iteration at a time.

As JavaScript developers and individuals, it can be difficult to swim against the tide in pursuit of more accessible experiences when you encounter resistance. Remember that you’re not alone, and even small contributions towards accessibility can add up to make a big difference for users over time.

The Right to Safety

Technology can cause actual harm to people. Like that time someone tweeted a strobing GIF at a reporter with epilepsy. Or that time an accessibility plugin was hacked to mine cryptocurrency, impacting thousands of web users across the world. Or those times app developers added location sharing features that could be used for stalking or bullying.

We can’t police what every user does or contributes online, but there are several areas in the software development life cycle where we can take care to prevent unsafe situations:

- Consider up front how your designs could be used by bad actors to cause harm and abuse. Not an expert? Hire people from marginalized communities to consult with you.

- Combat prejudice in machine learning by being transparent about training data and looking for hidden biases.

- Establish reasonable terms and moderation processes for user conduct with public policies and hold users accountable should they break that code.

- Follow security best practices and perform regular updates to avoid compromising the integrity of your deployed software.

Thoughtful AV Design

For users with seizure risk, vestibular disorder, traumatic brain injury or motion sickness, navigating sites and apps full of auto-playing videos and flashing animations can be a dangerous task. As developers of these sites and apps, it is possible to minimize harm and still implement beautiful and innovative designs. Warn users of sensitive or flashing material on loading screens, and avoid auto-playing media without user consent (this is also relevant to saving everyone’s data plans).

Animation developers can use the prefers-reduced-motion CSS media query or JavaScript function for Safari and Firefox to provide an alternate styling hook based on a user’s system preference. Configurable toggles at the individual site level are also a nice way to improve the experience for users with motion sensitivities, by allowing them to specify a preference for less animation (or some other style treatment) that can be translated into the visual design.

Protecting the vulnerable from malicious third-party code

There are still more ways that we need to keep our users safe. Vulnerabilities in third-party dependencies and libraries we use could put our users at risk by allowing unauthorized code to run on their system, so those libraries must be kept up to date with security patches or removed entirely. There’s a reason so many developers use ad-blocking software: today’s modern internet is full of tracking scripts making requests to questionable domains, as well as malicious or unwanted cookies.

We can do well by our users across the board by deploying secure sites over HTTPS, checking the integrity of scripts fetched over the internet, and following other security best practices. But there is also a business argument to be had: Do we take ad revenue from a sketchy third-party platform or is there something safer for our users, like a subscription-based model? A theme has emerged in this article: the strongest defense of user safety is to plan for it earlier in the product development life cycle.

The Right to Privacy

Our last look at how JavaScript can affect civil rights isn’t far from what we’ve discussed in the previous section; safety and privacy are quite intertwined. The same tracking scripts that store cookies on your computer “for convenience and basic functionality” can also sell your personal information to data aggregators and brokers. This is the price users pay for free social media applications, where their interactions and data are the products being sold. The least we can do is protect their legal right to privacy and allow them to opt out of data collection whenever possible. This is even more relevant after the passing of GDPR, which strengthened user privacy protections in Europe.

How we design and develop user contact forms in HTML can also have an impact on privacy. Consider whether you really need to include a gender field for basic functionality. Can you mark gender as optional, or add a non-binary option to it? We shouldn’t ask for gender data simply for tradition’s sake if the data isn’t actually necessary.

User privacy and the Accessible Object Model

Similarly, people don’t want to disclose their disability to you for basic site support. JavaScript developers are excited about the upcoming Accessibility Object Model, or AOM, which will provide more tooling for specifying accessibility information through scripting (as opposed to ARIA in HTML). Imagine being able to get a computed role or set an accessible name directly through a JavaScript API; that’s some of what AOM could do for you. It’s a very exciting proposal that could shape the web technology of the future; it has also produced some tension between user privacy and making complex accessibility use cases possible.

AOM has been compared to HTML5 geolocation, in that for privacy reasons, users would likely have to approve something in the browser to enable the new behavior. While the proposed design for AOM has evolved to use synthetic events, a permissions screen may still be a requirement in some cases. (There was also talk of making it HTTPS-only, but that’s pretty undecided at the moment.) When implemented in browsers, this powerful new tool must be used wisely, likely with redundant UI affordances to accomplish accessible tasks.

For example: a text input allows a user to search without agreeing to share their location through the geolocation API. Similarly, to use AOM features like Assistive Technology events, a user may need to approve the API. As developers, we need to provide UI affordances to complete the same task without requiring our users to sacrifice their privacy for access.

Conclusion

As you can probably gather by now, there are many ways we can impact our users’ civil rights for the better or worse. It might be overwhelming to try and hold all of these practices in mind, when everything inches out everything else for most important concern. When we say “accessibility first”, “mobile first”, “security first”, etc., we’re bound to fail or miss the mark in whichever ways weren’t prioritized. Some of the high-level items in this article might be out of your control as a developer, as well.

Therefore, it could help to start with something like this federal digital services checklist and adapt it to your team’s needs. Perhaps you can focus your attention to the relevant laws in your particular sector of technology. You should regularly evaluate how users’ rights will be impacted by each new design or feature you’re working on and start asking questions. In this line of thinking, you might ask things like:

- How would this feature impact the employment of people with disabilities?

- Are we leading all students to success through inclusive online education platforms and course materials?

- What privacy trade-offs are required in our APIs and user interfaces, and are we encouraging adequate alternatives?

- Are we introducing or tolerating bias in machine learning and algorithms, disproportionately impacting underrepresented groups?

- What processes do we have in place for reporting and escalating issues of user rights to privacy, safety, and access in our technology?

Fortunately, as JavaScript developers trying to respect our users’ civil rights, following industry best practices for accessibility, security, privacy and performance can get you quite far. Getting trained in these areas can provide practical tips for applying related principles: training has certainly helped to inform some of the information contained in this article. We have a huge impact over people’s lives as developers, whether we realize it or not. So let’s put our values to work!

When connecting the Attest desktop application to your device, you’ll notice the following message; “Attest will start capturing everything that’s displayed on your screen” when attempting to activate the service. This permissions prompt is allowing the Attest accessibility service to send interactive screenshots to the desktop application and nowhere else.

When connecting the Attest desktop application to your device, you’ll notice the following message; “Attest will start capturing everything that’s displayed on your screen” when attempting to activate the service. This permissions prompt is allowing the Attest accessibility service to send interactive screenshots to the desktop application and nowhere else.