Web accessibility is all about making sites and applications that everyone can use, especially people with disabilities. With a rather large list of competing priorities when building for the web, from accessibility to performance to security, it makes sense to automate parts of the process. Manual testing is a necessity for accessibility, however, a certain amount of the effort can and should be spent on automation, freeing up human resources for more complex or nuanced tasks.

Automated testing is a great way to start weaving accessibility into your website, with the ultimate goal of shifting left more and more towards the UX and discovery process. Automated testing definitely can’t catch everything, but it’s a valuable way to address easy wins and prevent basic fails. Build accessibility into your UI code, document features for teams, and ideally, prevent regressions in quality from deploying to production.

In this post, we’ll highlight the strengths and weaknesses of automated testing for web accessibility to both add value to your workflow and support people with disabilities.

Free humans up for more complex tasks

Many accessibility and usability issues require manual testing by a developer or QA person, while some can be automated. Ultimately, which automated tests you write will depend on the type of project: is it a reusable pattern library, or a trendy marketing site? A pattern library would benefit from a range of automated tests, from unit to regression; a trendy marketing site would be lucky to have any kind of testing at all.

When deciding what tests to automate, it helps to focus on the basics in core user flows. In my opinion, accessibility is a basic requirement of any user interface–so why not have test coverage for it? You can automate testing of keyboard operability and accessible component features with your own test logic, and layer on additional tests using an accessibility API for things like color contrast, labels, and ARIA attribute usage.

Think of it this way: can you budget the time to manually test everything in your application? At some point it does become cost and time prohibitive to test everything by hand and automation becomes a necessity. It’s all about finding a sweet spot with intentional test coverage that still provides value and a good return on investment.

Unit, integration, end-to-end, what the what?

There are many different types of automated tests, but two key areas for accessibility in web development are unit and integration tests. These are both huge topics in themselves, but the basic idea is that a unit test covers an isolated part of a system with no external dependencies (databases, services, or calls to the network). Integration tests cover more of the system put together, potentially uncovering bugs when multiple units are combined. End-to-end tests are a type of integration test, potentially even more broad to mimic a real user’s experience–so you’ll also hear them mentioned in regards to accessibility.

For accessibility, unit tests typically cover underlying APIs that plumb accessibility information or interactions to the right place. You should test APIs in isolation, calling their methods with fake data, called “inputs”. You can then assert these method calls modify the application or its state in an expected way.

it('should pass aria-label to the inner button', inject(function() {

var template = '<custom-button label="Squishy Face"></custom-button>';

var compiledElement = make(template);

expect(compiledElement.find('button').attr('aria-label')).toEqual('Squishy Face');

}));

You can unit test isolated UI components for accessibility in addition to underlying APIs, but beware that some DOM features may not be reliable in your chosen test framework (like document.activeElement, or CSS :focus). Integration tests, on the other hand, can cover most things that can be automated for accessibility, such as keyboard interactions.

It helps to have a range of unit and integration tests to minimize regressions–a.k.a. broken code shipping to production–when code changes are introduced. For tests to be useful, they should be intentional: you don’t want to write tests for tests’ sake. It’s worth it to evaluate key user flows and interactions, and assert quality for them in your application using automated tests.

Avoiding stale tests

No matter what kind of test you’re writing, focus on the outcome, not the implementation. It’s really easy for tests to get commented out or removed in development if they break every time you make a code change. This is even more likely with automated accessibility tests that your colleagues don’t understand or care about as deeply as you do.

To guard against stale tests, assert that calling an API method does what you expect without testing its dependencies or internal details that may change over time. You can call API methods directly in unit tests (i.e. “with this input, method returns X”), or indirectly through simulated user interaction in integration tests (i.e. “user presses enter key in widget, and X thing happens”). Testing outcomes instead of implementations makes refactoring easier, a win for the whole team!

No matter what kind of test you’re writing, focus on the outcome, not the implementation.

In reality, it can be difficult to maintain UI tests when there are a lot of design changes happening–that’s often why people say to avoid writing them. But at some point, you should bake in accessibility support so you don’t have to test everything manually. By focusing on the desired outcome for a particular component or interaction, hopefully you can minimize churn and get a good return on investment for your automated test suite. Plus, you might prevent colleagues or yourself from breaking accessibility support without realizing it.

To learn more testing fu, check out this talk from Justin Searls on how to stop hating your tests.

Keyboard testing & focus management

In a basic sense, the first accessibility testing tool I would recommend is the keyboard. Tab through the page to see if you can reach and operate interactive UI controls without using the mouse. Can you see where your focus is placed on the screen? Using only the keyboard, can you open a modal layer over the content, interact with content inside, and continue with ease upon closing? These are critical interactions for someone who can’t use a mouse or see the screen.

While the keyboard is a handy manual testing tool, you can also automate testing of keyboard operability for a user interface. For interactive widgets like tab switchers and modals, tests can ensure functionality works from the keyboard (and in many cases, screen readers). For example, you could write tests asserting the escape key closes a modal and handles focus, or the arrow keys work in a desktop-style menu. These are great tests to write in your application to ensure they still work after lots of code changes.

Unit testing focus

It’s debatable whether a unit test should assert actual focus in the DOM, such as document.activeElement being an expected element. Unit testing tools frequently fail at the task, and you’ll end up chasing down bugs related to your test harness instead of writing useful test cases.

You can try using something like Simulant, so long as keyboard focus is tested within a single unit, perhaps within an isolated component. In that case, go for it (and let me know which tools you end up using)! However, keyboard focus is often better tested in the integration realm, both because of ease in tooling and because a user’s focus frequently moves between multiple components (thus stepping outside the bounds of a single code unit).

Instead of unit testing interactions and expecting a focused element, you can write unit tests that call related API methods with static inputs, such as state variables or HTML fragments. Then you can assert those methods were called and the state changed appropriately.

Here’s a unit test example for a focus manager API from David Clark’s React-Menu-button:

it('Manager#openMenu focusing in menu', function() {

var manager = createManagerWithMockedElements();

manager.openMenu({ focusMenu: true });

expect(manager.isOpen).toBe(true);

expect(manager.menu.setState).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(1);

expect(manager.menu.setState.mock.calls[0]).toEqual([{ isOpen: true }]);

expect(manager.button.setState).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(1);

expect(manager.button.setState.mock.calls[0]).toEqual([{ menuOpen: true }]);

return new Promise(function(resolve) {

setTimeout(function() {

expect(manager.focusItem).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(1);

expect(manager.focusItem.mock.calls[0]).toEqual([0]);

resolve();

}, 0);

});

});

In contrast, while the above unit test asserts a focus manager API was called, an integration test for focus management could check for focus of an actual DOM element.

Here’s an integration (end-to-end) test example from Google’s howto-components:

it('should focus the next tab on [arrow right]', async function() {

const found = await helper.pressKeyUntil(this.driver, Key.TAB,

_ => document.activeElement.getAttribute('role') === 'tab'

);

expect(found).to.be.true;

await this.driver.executeScript(_ => {

window.firstTab = document.querySelector('[role="tablist"] > [role="tab"]:nth-of-type(1)');

window.secondTab = document.querySelector('[role="tablist"] > [role="tab"]:nth-of-type(2)');

});

await this.driver.actions().sendKeys(Key.ARROW_RIGHT).perform();

const focusedSecondTab = await this.driver.executeScript(_ =>

window.secondTab === document.activeElement

);

expect(focusedSecondTab).to.be.true;

});

For any part of your app that can be manipulated through hover, mousedown or touch, you should consider how a keyboard or screen reader user could achieve the same end-goal. Then write it into your tests.

Of course, what combination of unit and integration tests you write will ultimately depend on your application. But keyboard support is a valuable thing to cover in your automated tests no matter what, since you will know how the app should function in that capacity. Which brings us to:

Testing with the axe-core accessibility API

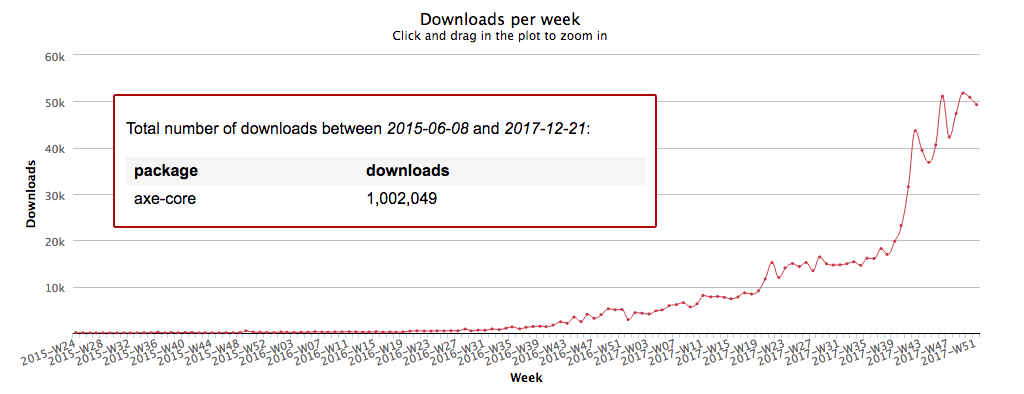

In addition to your app’s custom automated tests, there’s a lot of value in incorporating an accessibility testing API. Writing the logic and boilerplate for some accessibility-related tests can be tedious and error-prone, and it helps to offload some of the work to experts. There are multiple APIs in this space, but my personal favorite (and project I chose to work on full-time), is Deque’s axe-core library. It’s incorporated into Lighthouse for Google Chrome, Sonarwhal by Microsoft’s Edge team, Ember A11y Testing, Storybook, Intern, Protractor, DAISY, and more.

It really helps to test with an API for things like color contrast, data tables, ARIA attribute correctness, and basic HTML semantics you may have forgotten. The axe-core team keeps on top of support for various development techniques in assistive technologies so you don’t have to do all of that work yourself, something we refer to as “accessibility supported”. You can rely on test results to cover you in browsers and screen readers you might not test everyday, freeing you up for other tasks.

You can utilize the axe.run() API method in multiple ways: isolate the accessibility rules on a single component with the context option, perhaps in a unit test. Or, run the entire set of rules on a document in a page-level integration test. You can also look at the axe-webdriverjs integration, which automatically injects into iframes, unlike axe-core. Note: you can also use the aXe browser extensions for Chrome and Firefoxto do a quick manual test with the same ruleset, including iframes.

Here’s a basic example of using axe-core in a unit test:

var axe = require('axe-core');

describe('Some component', function() {

it('should have no accessibility violations', function(done) {

axe.run('.some-component', {}, function(error, results) {

if (error) return error;

expect(results.violations.length).toBe(0);

});

});

});

In contrast, here’s an axe-webdriverjs integration test for more of a page-level experience, which is sometimes better for performance when you’re running many tests:

var AxeBuilder = require('axe-webdriverjs'),

Webdriver = require('selenium-webdriver');

describe('Some page', function() {

it('should have no accessibility violations', function(done) {

var driver = new Webdriver.Builder().forBrowser('chrome').build();

driver.get('http://localhost:3333')

.then(function(done) {

AxeBuilder(driver)

.analyze(function(results) {

expect(results.violations.length).toBe(0);

done();

});

});

});

});

In both of these tests, a JSON object is returned to you with everything axe-core found: arrays of passes, violations, and even a set of “incomplete” items that require manual review. You can write assertions based on the number of violations, helpful for blocking builds locally or in Continuous Integration (CI).

It’s important to write multiple tests for each state of the page, including opening modal windows, menus, and other hidden regions that will otherwise be skipped by the API. This makes sure that you’re testing each state of the page for accessibility, since an automated tool can’t guess your intent when things are hidden with display: none or dynamically injected on open.

You can reference the axe-core and axe-webdriverjs API documentation to learn about all of the configuration options, from disabling particular rules, to including and excluding certain parts of the DOM, and adding your own custom rules. The upcoming 3.0 version of axe-core also supports Shadow DOM, which you can use with a prerelease API version or in the free aXe Coconut extension.

Find additional integrations and resources on the axe-core website: https://axe-core.org

Manual testing and user testing

It’s important to reiterate that automated testing can only get you so far in regards to accessibility. It’s no substitute for manual testing with the keyboard and screen readers along the way, including mobile devices. Some of these scenarios also can’t be automated at all.

You can cover the basics with manual testing and your automated tests. But to determine whether your app is actually usable by humans requires user testing. There’s a reason recent initiatives like ACAA (the Air Carrier Access Act) require user testing as part of their remediation steps.

Once your digital experience has stabilized a bit, it’s extremely important to user test with actual people, including those with disabilities. One exception to this might be in the prototyping phase, where you want to gather feedback from users before deciding on an official solution. In either case, organizations like Access Works can help you find users for testing. You should also consider remote testing to get the most out of your efforts.

Wrapping Up

Automated tests can help free up your team from manual testing every part of your app or website. At some point, automated tests become more efficient than having humans do everything. By being intentional with your test strategy and adding coverage for accessibility, you can communicate code quality to members of your team and potentially prevent regressions from deploying to production.

Valuable automated tests assert keyboard interactions, accessible API plumbing, and use of accessibility test APIs like axe-core to free you up from writing boilerplate code that’s easy to get wrong. However, automated tests are no substitute for regular manual testing yourself, and testing with actual users. A well-rounded, holistic testing approach is the best way to ensure quality is upheld in all stages of the process.

Don’t hesitate to reach out to me on Twitter if you have any questions or if you have a different approach! I’d love to hear about what works for you.

As my colleague Glenda Sims likes to say, “To A11y and Beyond!”